Editor’s note: This is one of my most popular posts of all time. This post was originally written several years ago (2019) and has been lightly updated to reflect developments in contemporary biblical scholarship, while preserving its original argument, tone, and structure. I’ve also recently written a piece on Genesis 1-11 here.

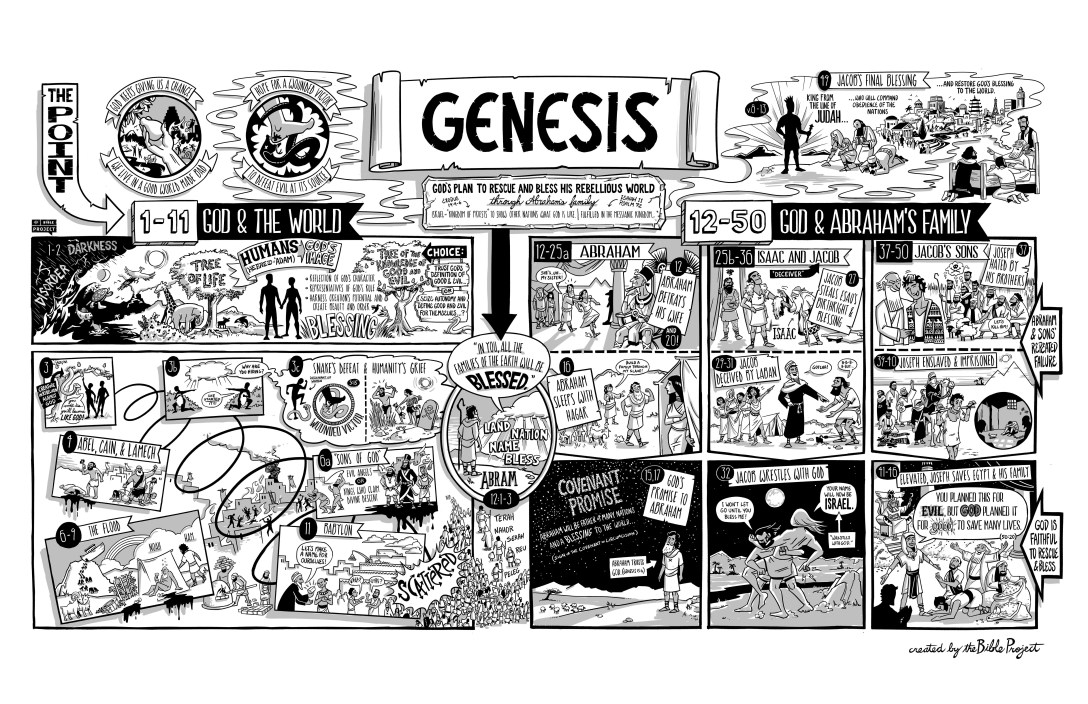

I also recommend watching this video on Genesis 1-11 by Bible Project if you’re more of a visual learner.

—

It really all began in Bible college.

I took Intro to the Old Testament and Intro to the New Testament in my first year. Naturally, in the first semester of our OT class, we began to comb through the Torah. But in my NT class, surprisingly, we spent more time in the Old Testament and then in the intertestamental period than I was expecting.

For a while, I was a bit confused. I didn’t want to spend time in Genesis 1–3 or Exodus. Let’s just talk about Jesus and the Gospels.

However, as time went on, I began to realise how important it was to understand that the New Testament is really just the culmination, fulfilment, and climax of everything the Old Testament was working towards. Essentially, the New Testament makes the most sense only in light of the Old Testament, in the same way that Avengers: Endgame only makes sense in light of all the prequels.

Thus, my love for the Bible truly started to evolve. I was now beginning to see that the Bible wasn’t just a collection of random independent books with neat little stories that we can enjoy or live by. Instead, it is, as the Bible Project often puts it, a unified story that leads to Jesus (Tim Mackie).

Eventually, it was Tim Mackie and the Bible Project that went even further in showing me the importance of the Old Testament story, particularly the role Genesis 1–11 plays. In fact, I’ve developed such a love for Genesis 1–11 that if I ever were to go into scholarship, it would have to be related to this section of Scripture. Until then, I must sate my curiosity with blogging about it.

Why Genesis 1–11 Matters

Genesis 1–11 is one of the most vital sections in all of Scripture. It contains the theological mythos of the world, the introduction of God, and the purpose of humanity. Every other story in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian New Testament can find its source in these eleven chapters.

In recent years, scholars have increasingly noted that Genesis 1–11 establishes creation as sacred space rather than merely material origin. Creation is presented as ordered, meaningful, and oriented toward God’s presence. This has led many to describe Genesis 1 as functioning like a cosmic temple narrative, with humanity placed within creation as God’s image-bearing representatives (John H. Walton; G. K. Beale).

Before jumping in, however, we must consider two things first: context and genre.

How to Read the Bible: Context, Audience, and Genre

When you study any section of the Bible, three questions must come to mind:

1. Who is the author, and who is the intended audience?

2. What is the context of this verse or passage, both canonical and historical?

3. What is the literary genre (historical, narrative, poetry, apocalyptic, wisdom, epistle)?

These questions help us move closer to the author’s intent and how the original audience would have received the text. Answering them doesn’t necessarily guarantee an accurate interpretation of Scripture, but it does get us a long way towards that goal.

Let’s take a simple example: the book of Romans.

We know the author (the Apostle Paul), the audience (Christians, likely both Gentiles and Jews in Rome), the date of the letter (AD 55–57), and the genre (epistle). While the theological purpose of Romans is still debated, these facts give us a fair understanding of what Paul was writing about, why he wrote, and how we should approach contested passages.

Because Romans is an epistle, we expect less symbolism and poetry and more precise theological argumentation. We can do the same work with the book of Genesis, although the results are more ambiguous (Tremper Longman III).

Who Wrote Genesis? Authorship and Tradition

Genesis is one part of a larger collection of books or scrolls known as the Torah or Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Authorship is tricky. Unlike Paul’s letters, Genesis does not identify its author. Furthermore, many books in the Old Testament did not have a single author in the modern sense. Literacy and record keeping in the ancient world were limited, often restricted to royal or priestly circles.

Tradition attributes Genesis to Moses, and not without reason. The Torah is frequently attributed to Moses throughout the Hebrew Bible (Josh 1:7–8; 2 Chron 25:4; Neh 13:1). The New Testament, and Jesus Himself, appear to attribute the Torah and Genesis to Moses as well (Matt 19:7; 22:24; Mk 12:26; John 1:17; 5:46).

Whether Moses literally penned every word is debatable, but what we can reasonably say is that Moses had a significant hand in the origins and shaping of the material (John Sailhamer). This naturally leads us into the question of context.

The Ancient Near Eastern Context of Genesis

If Genesis originates with Moses, then his cognitive environment would have influenced how the text was shaped. The Exodus story and Israel’s journey into the Promised Land draw deeply on the Genesis 1–3 narrative of God giving land (Eden) to humanity, testing obedience, and dealing with exile.

However, this is not the only context to consider.

The final form of Genesis, and the Torah as a whole, was likely shaped and compiled during or after the Babylonian Exile. This complicates matters, as there is a significant difference between the world of Genesis, the Exodus, and the exilic or post-exilic period.

Israel reading Genesis while living in exile would naturally interpret the text through that experience. Genesis 3, for example, tells a story of humanity being placed in land and then exiled from it due to sin. An exiled Israel would have immediately recognised their own story in that narrative (N. T. Wright).

Additionally, the Ancient Near Eastern world was the cultural backdrop of the Old Testament. Beliefs about gods, temples, family, relationships, and the cosmos all shaped how ancient authors thought and wrote. This cognitive environment inevitably influenced the biblical text (John H. Walton; Michael Heiser).

Abraham himself was called out of a pagan ANE world to form a distinct people for God’s purposes. Not everything Abraham did reflects ideal righteousness. He, like Israel after him, wrestled with shedding cultural norms in order to live faithfully before God.

What this suggests is that God deliberately used each author’s cognitive environment as a means of shaping His revelation. God speaks into real history, through real cultures, without collapsing into them.

What Genre Is Genesis 1–11? Myth, History, and Theology

Genesis as we have it today likely passed through Moses, was preserved through oral tradition, and was finally shaped in or after the Exile. Chapters 12–50 can be understood as Israel’s origins, while chapters 1–11 function as the origins of the whole world.

Broadly speaking, Genesis is historical. However, ancient history and modern history are not the same thing. The ancient world preserved history differently, with a far greater emphasis on meaning than on exhaustive detail.

I would categorise Genesis 1–11 as theological history told through mythic and literary forms.

By this, I do not mean that Genesis 1–11 did not happen. Rather, the primary purpose of these chapters is to convey divine truth. In this context, mythic does not mean fictional. It refers to the use of story, symbolism, and archetypal language to communicate reality at a deep theological level (Tremper Longman III).

The events occurred, but they are presented in a way that draws out theological meaning rather than providing a modern historical account. As Longman succinctly puts it, “The book of Genesis is not a history-like story but rather a story-like history.”

Summary

To summarise Part I:

Authorship: Genesis likely originates with Moses, but its final form was shaped during or after the Babylonian Exile.

Context: The Ancient Near Eastern world, the time of Moses, and the experience of exile all shape how the text should be understood.

Genre: Genesis 1–11 is best read as theological history communicated through rich, mythic, and literary narrative forms. It tells the story of the world’s beginnings in order to reveal divine purpose, not modern scientific detail.

In the next part of this series, we will begin by looking closely at Genesis 1.