There is a kind of spiritual exhaustion that settles into people who genuinely want to follow Jesus but can’t seem to make themselves “better”. They are not defiant. They are not lazy. They are not looking for loopholes. They are simply tired of carrying an inner world that feels frayed, reactive, anxious, or numb. Unfortunately, what they often receive from the Church is more “weight”.

Try harder. Pray more. Read your Bible. Stop doing that. Start doing this. Be disciplined. Be holy.

Those words can be true, as far as they go. But they can also be cruel when they are spoken to someone who is not yet safe in their own skin. We keep asking wounded people to behave like healed ones. We keep demanding fruit from branches that are still snapped at the core.

The tragedy is that we call this “discipleship”. However, Jesus rarely starts where we do. Instead, He begins with restoration. He begins with presence. He begins with the gentle work of putting a human being back together.

And only then, sometimes quietly, sometimes with clarity, other times with mystery that requires faith, He invites them into a new way of living.

Healing comes before obedience.

Not as a modern self-help slogan. Not as an excuse to ignore holiness. But as a thoroughly Christian ordering of grace, truth, and transformation.

The Order of the Gospel

When the Church reverses the order, people either become hypocrites or casualties.

Some learn to perform. They polish the outside. They memorise the right phrases, adopt the right posture, and keep the right habits. But the inner world remains untouched. Desire stays bent. Shame remains in control and untouched. Anxiety continues humming under the surface. They become “good” in public but brittle in private. Their faith becomes performative image management.

Others collapse. They try to obey, fail, repent, try again, fail again. Eventually, they decide they are broken beyond repair, that God must be disappointed, and that everyone else must be doing Christianity better than them. They’re exhausted. They adopt impostor syndrome. The spiritual life becomes a treadmill powered by fear. Neither of these outcomes resembles the peace of Christ.

The gospel is not God issuing demands from a distance. It isn’t behaviour management. The gospel is God drawing near. It is God’s life moving toward our death. God’s wholeness moving toward our fracture. God’s love entering the places where we have learned to survive and transforming us from the inside out.

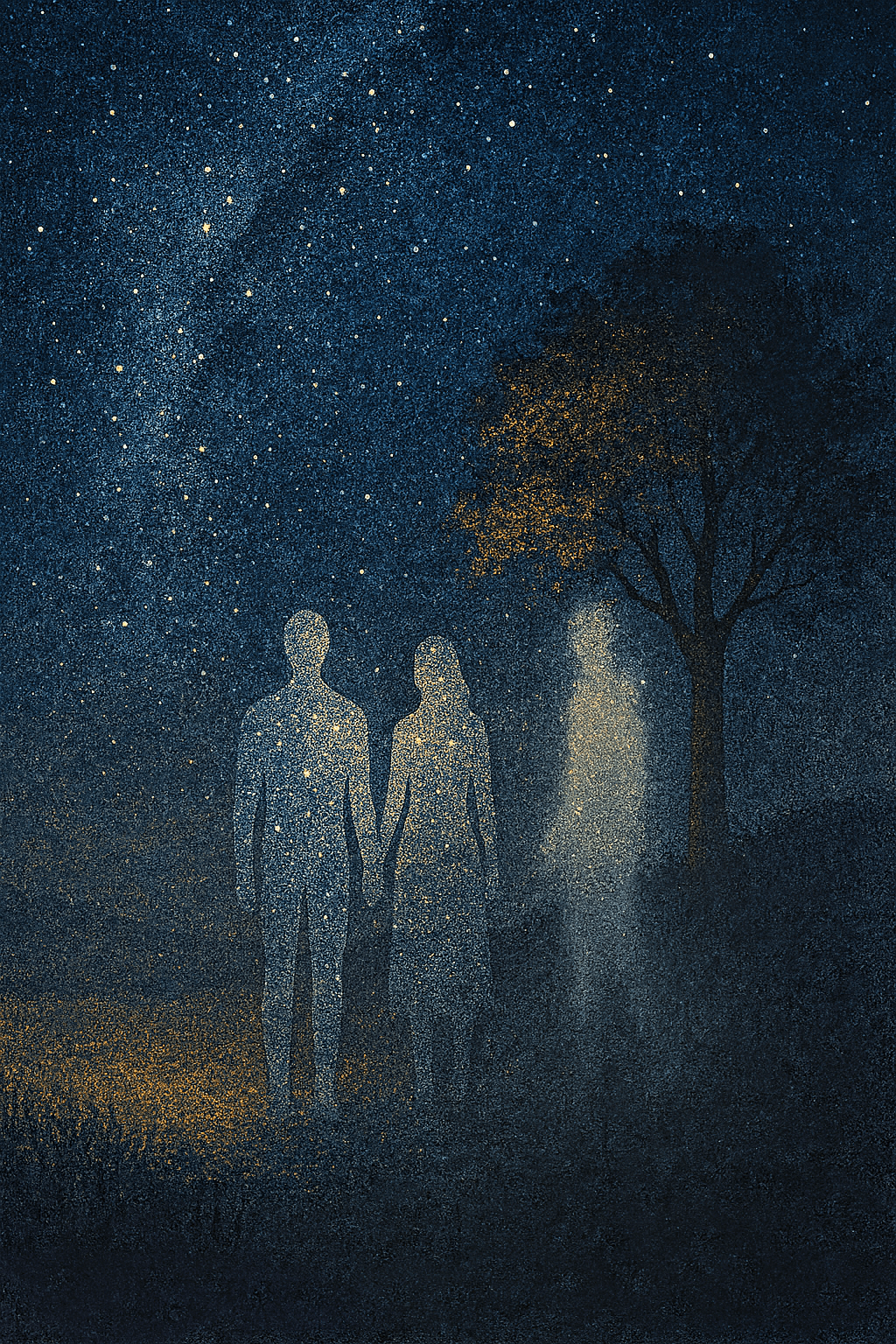

The Christian story begins with the incarnation: God in flesh. God in weakness. God in the ordinary and the wounded. Before Jesus teaches a single sermon, he is already saying something with His presence: you do not have to climb your way up to me. I have come down into you. We tend to treat obedience and rules as the entry point into transformation (though we’d never admit it). However, Jesus treats God dwelling among us as the entry point into the Kingdom.

Jesus Heals First

If you read the Gospels with even a little attention, a pattern emerges. Jesus does not primarily meet people with a checklist. He meets them with a kind of attention that feels like warm sunlight on a winter morning.

He touches lepers. That alone is a theological act. The body that society calls untouchable becomes, in Jesus’ hands, a place of divine contact and healing. Before the man has a new life, he has a new experience of belonging. Before he changes, he is met. He restores a bent-over woman and calls her “daughter”, publicly naming her dignity. He does not begin with a lecture about her habits. He begins by working on the inside and then the outside. Christ sits at the table with sinners, not as a tactic, but as a declaration: my holiness is not contaminated by your mess, and my love is not withheld until you are clean. I am here.

Even when Jesus confronts behaviour, he often does so after re-establishing safety. Consider Peter. Peter fails loudly. He denies Jesus, not once, but repeatedly, and then collapses into shame. After the resurrection, Jesus does not begin with punishment. He begins with breakfast. A fire. Fish. Ordinary warmth. Then, and only then, he asks Peter the most restorative question imaginable: do you love me? Not “why did you do it?” Not “how could you?” But: do you still want me? Is the relationship still alive?

It is psychologically sophisticated and spiritually profound.

Jesus is not ignoring sin. He is going beneath it.

Because sin is rarely (if ever) just about behaviour. It is often the surface, or the fruit of something deeper: fear, pain, disintegration, misdirected desire, unmet longing, a nervous system stuck in survival. Behaviour is the fruit, brokenness, and the things that enslave us are the root.

Jesus treats the person, not just the symptom.

Why Obedience Fails Without Healing

We have to be honest about how humans work. God made us embodied. That means spiritual formation is not only about ideas or willpower. It involves the mind, the body, memory, attachment, desire, and the patterns our nervous system has learned for staying alive.

Trauma does not only happen when something terrible happens. Trauma also happens when something good should have happened and did not: safety, protection, nurture, comfort, stable love. The wounds of absence can shape a person as much as the wounds of violence.

When the inner world is formed under threat, the body learns to survive. It develops strategies: people-pleasing, controlling, numbing, avoiding, performing, disappearing, and exploding. These behaviours are never acted out in a vacuum. They are learned responses to pain, suffering, and brokenness.

If you tell a person like that to “just obey”, you might get compliance, but you will not get transformation. Compliance is fear dressed in religious clothes. It looks like holiness from a distance. Up close, it is often anxiety and depression.

In these cases, obedience does not heal. It intensifies the fracture.

This is where shame becomes especially dangerous. Shame is not simply “I did wrong”. Shame is “I am wrong”. It collapses the whole self into failure. It makes the soul hide. It makes vulnerability feel like a threat. It teaches people to lie, even to themselves, because telling the truth would feel like committing suicide. You can’t build a mature Christian life on shame. You can build a controlled community with it. You can build a performance culture. You can build a church that looks clean (but is dead inside). But you can’t build the kind of people Jesus makes: honest, free, humble, resilient, tender, brave.

Obedience without healing is not sanctification. It is behaviour management. It is pruning leaves while the roots rot.

Sin as fracture, not merely rule-breaking

This is one of the places where theology and psychology can actually hold hands, if we let them.

Sin is real. Scripture does not downplay it. But sin, in the biblical imagination, is not only the breaking of rules. It is disunion. It is misalignment. It is a turning inward that fractures our capacity for love. It is a distortion of desire. It is a bondage to the powers that dehumanise humanity and cause fear, shame, death, violence, and idolatry. When sin is understood only as legal guilt, the solution becomes a legal transaction. When sin is also understood as wound and bondage, the solution becomes healing and liberation. This is why the gospels feel like a rescue story, not a courtroom drama.

Jesus does not merely announce forgiveness. He casts out what oppresses. He heals what is broken. He restores people back into community. He re-humanises them. He makes them whole. Forgiveness is a doorway back into right relationship with God, the world and even yourself.

And it is in relationships where true healing happens.

If God’s goal is union, then God’s work will look like reconciliation, restoration, and integration. God does not just want “better behaviour”. God wants you back. God wants your heart unknotted. God wants your body to breathe again. God wants your desires to become truthful. God wants your life to be free enough to love.

This is not therapeutic Christianity. This is Christianity as it always was when it was at its best – salvation as becoming truly human.

What Obedience Looks Like After Healing

This is where some people get nervous. They hear “healing comes first” and assume it means “obedience does not matter”. It matters. But it matters as fruit, not as an entry fee.

There is a kind of obedience that is fundamentally self-protective. It obeys to avoid punishment, to maintain image, to manage anxiety, and to stay in control. It is often rigid. It struggles to be honest. It is terrified of ambiguity. It becomes harsh toward others because it is harsh toward itself. It’s bitter, judgmental, scared and closed off.

Yet there is another kind of obedience. It is both softer and stronger. It obeys because it trusts. It obeys because it has been loved. It obeys because desire has been sufficiently healed to want the good without being forced into it. This kind of obedience is not held onto; it is surrendered.

It is not performative. It is quiet. It is not obsessed with being seen as “right”. It is more concerned with being real. It is what love looks like when the soul is no longer defending itself.

This is why Jesus speaks so often about trees and fruit. Fruit grows when the conditions are right. It is not manufactured through pressure. You can tie fruit to branches with a string, but everyone can tell it is fake. Real fruit comes from life moving through the tree.

Union produces obedience the way sunlight produces growth. Not instantly. Not perfectly. But organically.

A Pastoral Reorientation

If healing comes before obedience, then a lot of our church instincts need to be re-examined. It means we should stop treating people as problems to be fixed and start seeing them as souls to be loved. It means we should be slower to correct and quicker to listen. It means we should create communities where confession is not a public execution but a doorway into mercy and change. It means we should stop confusing “high standards” with spiritual maturity. Many people can keep standards. Fewer people can become humble. Fewer still can become gentle. The Pharisees obeyed plenty of rules. Jesus still called them blind.

It also means we need to distinguish between conviction and condemnation.

Conviction is usually specific. It has clarity. It leads toward life. It can be painful, but it does not crush the self. Condemnation is vague. It is global. It tells you that you are the problem, that you are unworthy, that you will never change. One draws you into God. The other drives you away.

If your spirituality leaves you terrified, brittle, performative, and exhausted, there is a good chance you are obeying without healing. Or you are trying to heal yourself through obedience. And it will not work. It cannot work. That is not how grace works.

Grace is not God lowering the standard. Grace is God raising the dead to it. That includes the dead places in us. The numb places. The angry places. The frightened places. The places we learned to hide. Jesus does not stand at the door of those places shouting instructions; He enters them. Jesus sits there with the patience of God. He touches what is untouchable, and He speaks to what has been silenced.

He stays.

And from that staying – slowly, obedience begins to make sense again. Not as a threat. Not as a way to earn belonging. But as a response to love.

A Contemplative Closing

There is a gentleness in God that we often mistake for permissiveness. It is not permissiveness. It is wisdom. God knows that fear cannot heal fear. God knows that shame cannot heal shame. God knows that woundedness cannot be commanded into wholeness. So God comes near. He heals. He restores, and He puts the pieces back together.

And then, like a path appearing under your feet, a new way of living opens. Not because you finally became strong enough. But because you were met by a person strong enough to hold you and see you while you learned how to walk again.

If you are tired, if you feel stuck, if obedience feels like grinding your teeth in the dark, consider this: maybe the invitation in front of you is not “try harder”. Maybe it is “come closer”. Maybe the next faithful step is not another vow of effort, but a quiet act of consent.

“Lord, heal what is beneath my habits.

Lord, meet me where I am fractured.

Lord, restore the parts of me that have been surviving.

And let obedience be fruit, in season, from a life finally learning how to breathe.”

Amen