The Gospel Begins with Wonder, Not Sin

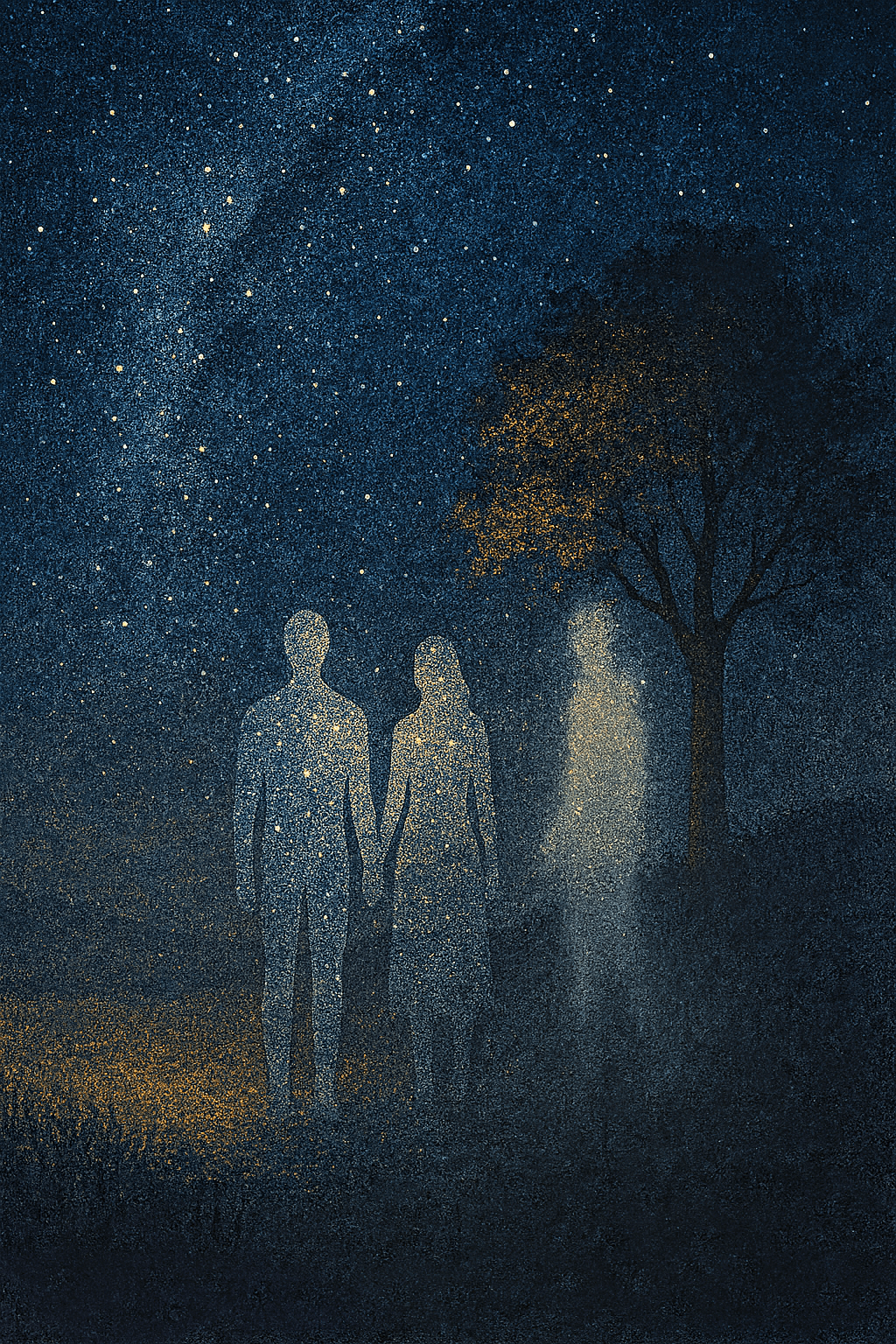

The gospel does not begin with sin. It begins with wonder.

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). From the first moment, creation was spoken into being within God’s own presence. Life emerged as song, at his call, not apart from him but held inside his life. Mountains rose and oceans gathered, their beauty already shimmering with his nearness.

And then God stooped low, pressing his breath into dust. Humanity came alive, not only because of lungs and blood, but because every heartbeat throbbed with the life of God. As Paul would later say, “In him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

The world has never existed outside of God. We dwell in him, even as he dwells in us. Every breath you take is not just survival. It is communion.

Created to Share in the Divine Life

“Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness” (Genesis 1:26). From the beginning, we were not just creatures surviving on borrowed breath. We were made as mirrors of the divine, meant to shine with another’s glory.

The apostle Peter writes, “we were made to be partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). Creation is not simply about survival or usefulness. It is about communion. It is about living our lives inside the very life of God.

Irenaeus of Lyons once said, “The glory of God is a human being fully alive, and the life of the human consists in beholding God.” That is creation’s secret. We were meant to live every breath as communion, every heartbeat as sacrament. The mystics remind us again and again that the world is charged with God. Meister Eckhart could say that every creature is “a word of God and a book about God.” Before sermons, before catechisms, creation itself was already preaching. “The heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19:1).

What would it look like to see creation, the tree outside your window, the face across the table, as a word of God spoken to you?

The Fracture of the Fall

But then the story bends.

The serpent’s whisper is subtle. “You will be like God” (Genesis 3:5). The tragedy is that likeness to God was already our inheritance. What could have been received through communion, we tried to seize through grasping. What was meant to be given in love, we reached for in desire.

And in the reaching, something broke. Their eyes opened, but not to glory. Only to shame (Genesis 3:7). Hearts that once lived open to God turned inward and hid from the Presence that still walked in the garden (Genesis 3:8). Communion became exile.

Sin as Broken Communion and Blindness

For the mystic, sin is not simply breaking rules. It is breaking communion. Augustine captures it in his Confessions: “You have made us for Yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.” Restlessness is the echo of what we lost. It is the ache of a heart turned from the fountain of life, thirsting for water while standing beside the spring. Jeremiah gave it his own words: “My people have forsaken me, the spring of living water, and dug their own cisterns, broken cisterns that cannot hold water” (Jeremiah 2:13).

Gregory of Nyssa, the great contemplative, saw humanity as created for an endless ascent into God. Our destiny was always to go deeper into beauty without end. But in the fall, our gaze turned from the Infinite to ourselves. We lost our horizon. We curved inwards. The soul that was meant to climb into God instead closed in on itself.

This is why the mystics often speak of sin as blindness. John of the Cross wrote of the dark night, when the soul cannot perceive the light even though it surrounds her. That is Eden’s exile. The Presence never left. The light still shines in the darkness, but our eyes have forgotten how to see it (John 1:5).

God’s Presence Remains After the Fall

And yet, even here, grace remains.

God does not abandon Adam and Eve to their shame. He clothes them with garments (Genesis 3:21). He keeps walking, keeps calling: “Where are you?” (Genesis 3:9). This is not the cry of a detective chasing criminals. It is the voice of a lover searching for his beloved. Even in exile, God follows. Even in our turning, he does not turn.

Julian of Norwich, reflecting on human sin, once heard Christ speak these words to her: “Sin is behovely, but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” For her, sin was not the end. It was the place where mercy would be revealed.

We are dust, but dust still held by God’s breath. We are exiles, but never outside his gaze. The wound is real, but so is the promise. The God who made us to share in his own life will not rest until we do.

A Contemplative Practice

Take a few minutes today to sit quietly. Place your hand on your chest. Feel your breath rise and fall. With each inhale, pray: “In You I live.” With each exhale, pray: “In You I rest.”

As you breathe, remember that the first breath you ever received was God’s. Even in exile, his life still holds you.