In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters. – Genesis 1:1-2

A long time ago before I became a Christian, I remember dating a girl who’s family were hardcore believers. I remember one day being at their house, bored, and picking up a Creation magazine. Two things stuck out to me. First, that the earth was around 6000-10,000 years old and second that they didn’t believe aliens existed. Immediately I knew they were crazy. However, it wasn’t long until I thought these things myself. When I became a Christian, I hit the ground running with the Scriptures. I soaked up everything it had to say and just believed what I thought it was telling me. For most of my Christian life, I believed that God created the earth around 6000 years ago, that there was a real talking snake in the Garden, and that ideas like evolution were a lie cleverly constructed to deceive the world into believing that God doesn’t exist. I was taught by many people (people who are still dear friends today) that unless you believed these things you weren’t taking Jesus, the Bible or the Faith seriously. So I joined their tribe. I often went street preaching, seeking to debunk evolution and turn people to Jesus. For me, atheism and evolution went hand in hand, and if you could disprove one, the other would fall. Sure, I had heard about Christians out there who believed in evolution (they’re known as theistic evolutionists). However, they were considered liberal, twisting the Scriptures, compromising and it probably wasn’t long until they walked away from the Faith altogether. Since then, a lot has changed. Bible college set me on a trajectory of seriously studying the Scriptures in its original context and genre. I remember quite clearly that the first theological position that shifted was my eschatology. I went from being a Premillenail Dispensationalist to a Convenential Amillinealist. The next thing that started to change was my approach to the Scripture itself. I went from reading Bible verses in isolation from one another to seeing huge thematic threads that reverberated throughout the entire Biblical narrative (I came to know this as biblical theology).

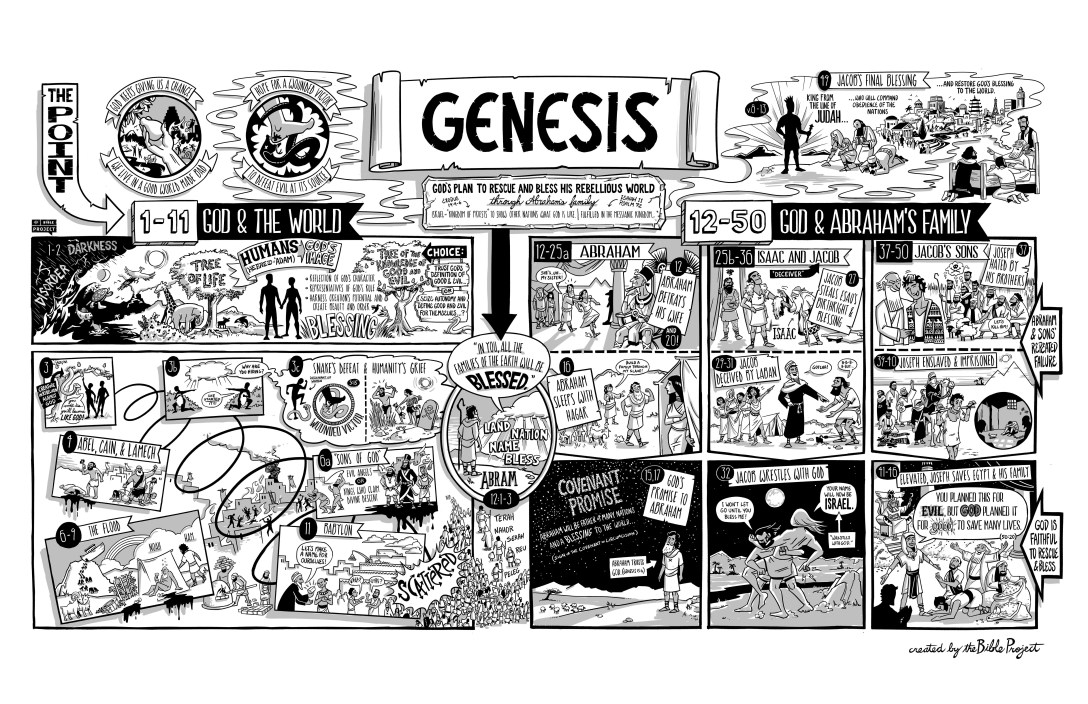

I began to understand the importance of context, genre, audience, authorship and to look for the authors intent (much of which I discuss here). Huge biblical themes like temple and sacred space, priesthood, union with God and much more, lit up the Bible as it began to sing to me a sweet alluring song that I haven’t been able to get out of my head to this day (not that I’ve tried). Eventually, I came across Tim Mackie and the Bible Project. They kept pointing out how important the story of Genesis 1-11 was for the entire biblical narrative, and wow was I amazed. Coupled with what I was learning at college, these guys turned the Bible from Netflix into 4k VR surround sound where, at times, it was almost like I could touch God Himself through the very pages I was reading. Now, as a result of all this, over the last three years or so I’ve shifted in my view of Genesis 1. Let’s explore.

Genesis 1 has been the subject of much speculation and debate for thousands of years. Each generation or era has a different take on what’s happening in the text, and I actually don’t think that’s a horrible thing. I believe God intends for us to reflect on whatever it is we’re reading in the Bible into our own context and live out the implications as God’s people. However, this shouldn’t be at the expense of the original intended meaning of the text. As far as I can tell, I see three main theological themes being explored in the first chapter. 1. God and who He is. 2. The ordering or construction of sacred space. 3. The establishing of humanity and their vocation in relation to God, sacred space, and the created order.

When we turn to the first page in the Bible, the very first thing the author wants us to notice is that there is a god and that this god created the heavens and the earth. Who is this god? This is where context is so important. If Moses wrote Genesis (I discuss authorship in a previous post), then his cognitive environment would have shaped his understanding of who this god was. For Moses and the Israelites in the Exodus events, the same God who brought them out of Egpyt was the same God who was the Creator in Genesis 1. This can be further supported by the use of the title “LORD God” in Genesis 2:4 (and onwards) where the author seems to be making an emphatic claim that this is indeed Yahweh Himself. The God of Israel is the God of the entire cosmos.

Just this line of thought alone has some profound implication for its readers. The most obvious is that God doesn’t merely create the universe, order it, and leave it to its own devices (deism). Instead, if this god is Yahweh Himself, we see that He is always at work throughout human history. God is both transcendent and immanent. He is distinct from His creation but is at work in it and often through it to bring about the redemption of a fallen world. The New Testament later picks this up by throwing Jesus into the mix (see: John 1 and Col 1:15-17).

Furthermore, in a polytheistic world, the idea that one God created the cosmos would have been a little edgy. In the ancient near eastern world (ANE), there were many other creation narratives, each depicting a council of gods creating the cosmos, usually chaotically, through violence and battle. Instead, God here simply speaks, and there is light, stars, animals etc. Very chill. To me, this says something about God’s character. Rather than having chaos reign, God is all about order, peace, shalom. In fact, this can be further supported by the use of the word create. This leads me to my next point. Order out of chaos and sacred space.

Here is where I blend a few ideas together. First, we read that the earth was formless and void. The Hebrew wording here can be translated as wild and waste, desolate and chaotic. Picture, if you can, a tumultuous watery wasteland that continuously churns and destroys. This was the state of the world before day one. Immediately the readers would have picked up on what was happening here. In the surrounding ANE world, there were plenty of creation narratives where chaotic and wild waters were to be overcome by the gods. It’s where the great leviathan dwelt, chaotic and dark sea creatures at odds with the plans of the gods (see the Enûma Eliš as an example). To the ANE world, dark, chaotic waters and leviathan were something to be feared, yet in the text, God simply brings order out of this chaos by speaking, unlike the ANE gods that wared over it. Furthermore, the leviathan was made to be a good creature, not an evil one in Genesis 1:20-23 (c.f. Ps 104:26). Similarities? Yes. Absolutely. It goes without saying that we’re going to find similarities between people groups in the same cognitive environment.

The differences, however, are important. Instead of God having to fight or war for lordship over the chaos and darkness, He is lord from the very beginning. The chaos creatures are actually His, and so are the waters. They’re subdued and ready to be moulded in the hands of the Creator. From here, God takes the wild watery wastes and uses them to form His sacred space – temple.

John Walton in his book “The Lost World of Genesis 1” argues that the Hebrew word for “created” in Genesis 1:1 shouldn’t be understood as ex nihilo (creation out of nothing), rather it should be understood that God orders the cosmos into a cosmic temple (sacred space). I recommend you read his book and wrap your head around the full argument. From what I’ve learned from him and other resources I concur. The ANE world was more concerned with function and order then they were about the material origins we’d usually read into the text. One analogy Walton uses is the difference between a house and a home. The way we usually read the text is like building a house. We place down the foundations, the walls, roof etc. Where the ANE was more interested in a home with furniture, food etc. A home is where one thrives, lives and flourishes, the other is more about material origins. This is likely what’s happening in the text. The author is more interested in function and home in the sacred space God is about to order, rather than the material origins of the universe. In this blog, I explore the theme of temple and how it relates to the biblical story. In the next post, we’ll explore more about the theme of temple and how it relates to what’s happening here.

So to wrap up this part of the series:

- The god in Genesis 1 is Yahweh. He is the sole creator, sustainer and Lord of life.

- The earth was in a wild, dark and chaotic space then God starts to order it.

- God is arranging a sacred space or temple.