What if the greatest misunderstanding in modern Christianity is not about morality or politics but about the gospel itself? What if the good news we share is smaller than the one Jesus announced?

We often describe the gospel as a private story about forgiveness, heaven and personal salvation. Yet in Scripture the gospel is something far larger. It is the announcement that God reigns. It is not only about the state of our souls but about the state of the world. It is a claim about reality itself, a declaration that creation has a rightful King.

And that claim changes everything.

The Gospel as Royal Proclamation

In Hebrew, the word for good news is besorah, a royal announcement of victory (Isaiah 52). In Greek, it is euangelion, the public declaration that a king has triumphed (Mark 1).

Imagine an ancient city under siege. The people wait behind their walls, anxious for word from the battlefield. Then a runner appears on the hills, covered in dust, shouting between breaths, “Good news! Victory! The king has won!”

That was euangelion. It was not advice or philosophy but the kind of announcement that makes the world different because it is true.

When Isaiah writes, “How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news, who say to Zion, ‘Your God reigns’” (Isaiah 52:7), he is describing that runner. The heart of the gospel is that Yahweh has returned to rule His world.

Centuries later, Jesus begins His ministry with the same royal declaration: “The time is fulfilled, and the Kingdom of God has come near. Repent and believe the good news” (Mark 1:15). He is not inventing a new religion but announcing that Israel’s long-awaited hope has arrived. God’s reign is breaking in.

The Kingdom Woven into Creation

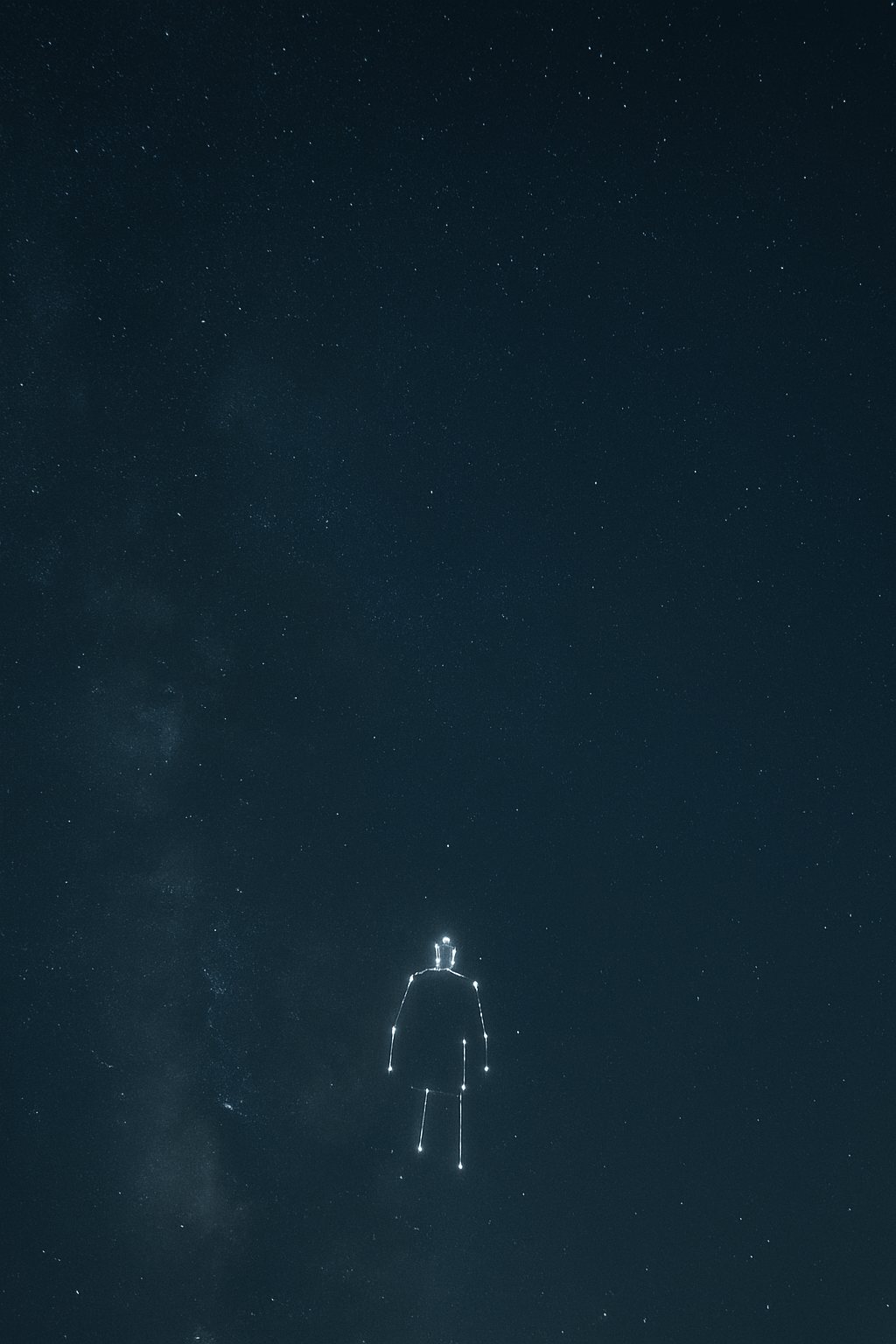

The story of God’s Kingdom does not begin with Jesus. It begins in Genesis, where the rhythm of creation beats with divine rule (Genesis 1-2).

In the first three days, God shapes the realms of creation: light and darkness, sky and sea, land and vegetation. In the next three, He fills those realms with rulers: the sun and moon, the birds and fish, the animals and humanity.

The story is one of order and relationship. God reigns by creating and sharing. His rule is not control but care. Humanity, made in His image (Genesis 1:26-28), is invited to share that reign and to reflect His goodness, justice and creativity into the world.

To rule, in the biblical sense, is not to dominate. It is to cultivate. It is to join God in the work of making the world flourish.

The Kingdom of God is not a future dream. It is the structure of reality itself. Heaven and earth were made to live together (Genesis 2:15). Sin fractures that harmony, but the mission of God is to bring it back, to restore what was lost and heal what was broken.

Jesus: The King in Person

When Jesus announces the Kingdom, He is not speaking about a distant future or an inner feeling. He is proclaiming a change of reality. Where He walks, heaven and earth meet. The sick are healed, the outcasts restored, and the powers of darkness pushed back (Luke 4:18-9; Matthew 12:28).

At the cross, the world’s false rulers do their worst. Yet in that act of humiliation, the true King is enthroned (John 19:19). Through resurrection, His victory is declared not over Rome but over the powers that hold all creation captive: sin, death and decay (1 Corinthians 15:25-26).

Paul’s hymn in Colossians captures it perfectly:

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. In Him all things hold together. Through Him God was pleased to reconcile all things, whether on earth or in heaven” (Colossians 1:15-20).

This is not private spirituality. It is cosmic renewal. Christ holds the whole story together. In Him, the Creator’s original dream of heaven and earth united is set in motion again.

The People of the King

The early Christians understood this far better than we often do. They did not treat faith as an escape plan but as a new citizenship (Philippians 3:20). They believed that the Spirit who raised Jesus now lived within them, calling them to live as citizens of a new world (Romans 8:11).

Every act of love and hospitality, every work of justice or reconciliation, was an echo of the good news. It was a small proclamation that “our God reigns” (Isaiah 52:7).

The Kingdom is not confined to heaven or to church gatherings (though, as I argue elsewhere, the church should be a slice of the new creation). It is wherever the reign of Christ shapes hearts and habits, homes and communities (Matthew 5-7). It is wherever people reflect His character in the ordinary and the everyday.

N. T. Wright once said that the church does not bring the Kingdom by force; it embodies it by faithfulness. That is the invitation: to embody the reign of the King.

The Kingdom Completed: New Creation

The story of Scripture ends where it began, but expanded and fulfilled. A garden becomes a city. Heaven and earth are reunited.

John’s vision in Revelation captures it:

“I saw a new heaven and a new earth… and I heard a voice from the throne saying, ‘See, the home of God is among mortals’” (Revelation 21:1–3).

This is not an escape from the world, but rather its healing. The good news is not that we leave creation, but that God enters into it and restores it (Romans 8:19–21).

Every tear will be wiped away. Every injustice will be answered. The scars of the old world will become the beauty of the new (Revelation 21:4–5). The reign of God will fill everything.

Living Under His Reign

If the gospel is the announcement that God reigns, then discipleship is the art of living as if that reign were already true (Matthew 6:10). Repentance means realigning with reality, turning from our small empires to join the life of the King.

Faith is allegiance. It is trust that God’s rule is good and that life under His care is freedom, not bondage (John 8:36).

Every prayer, every meal, every act of mercy or courage is a way of saying again, “Your God reigns” (Isaiah 52:7).

The gospel is not good advice. It is good news.

And that news is this: heaven has begun to come down to earth. The reign of God is arriving quietly, patiently, beautifully, until all things are made new.